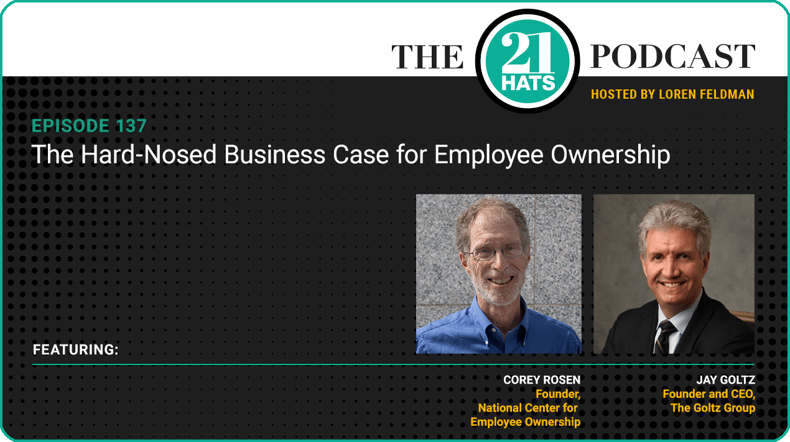

This week, Jay Goltz explains how he got interested in selling a percentage of his business to his employees and why he quickly lost interest once he started reading books, attending seminars, and talking to accountants and lawyers who specialize in employee stock ownership plans. To Jay’s ear, they all made ESOPs sound expensive, complicated, and risky. This was not something he needed to do. So why go to the trouble? Why take the risk? But he kept asking questions, and over time, he sensed that many of the problems he was being warned about didn’t have to be problems. As of now, he’s pretty much concluded that an ESOP could help him secure retirement for his employees while generating more profit for his business. In fact, he says, “I’m confident I can make more owning 70 percent of the company than I am now owning 100 percent.” But he still has a few lingering questions, which is why we invited Corey Rosen to join the conversation. Corey helped draft the legislation that created ESOPs, he’s the founder of the National Center for Employee Ownership, and he literally wrote the book on how the plans work. All of which led to an inevitable question for both Jay and Corey: If ESOPs are so great, why are there so few of them?

— Loren Feldman

This content was produced by 21 Hats.

See Full Show Notes By 21 Hats

Key Takeaways:

How do you know if an ESOP is right for your company?

3 questions Corey Rosen suggests leaders ask themselves when considering an Employee Stock Ownership Plan.

1. Are you profitable enough so that you could use future deductible profits to buy out your shares over time and still have enough money left over to run your business successfully (even though it’s on a tax-preferred basis)? If you don’t have both of those, there’s really not a way your company could take on an ESOP.

2. If you’re leaving, do you have successor management? Same kind of question, really, that a bank would ask. They want to know if you’ve got successor management in place for obvious reasons. How will the company be run when you step out?

3. Are you big enough? It costs money to set up an ESOP, and it could cost anywhere from $100,000 to $500,000, typically, for businesses that are the typical ESOP candidates. It depends in part on the complexity of the transaction, the size, and other factors. Realistically, if you sell your business to anyone else, it’s going to cost probably as much money, and often more, because when you do sell to someone else, if you’re using an M&A advisor or a broker, they’re going to charge a success fee. And most ESOP deals don’t involve a success fee. Some do. But that’s a percentage of your transaction.

You can't pick and choose how much stock gets allocated to employees – ESOPs come with rules.

There’s one other consideration that people should understand when they’re making the decision, which is that ESOPs come with rules about how the stock gets allocated to people. And I have talked to people over the years who say, “I want employees to own the company. I love all the tax benefits. But I am not comfortable with not being able to pick and choose who gets how much stock.” And it’s a small number of people who feel that way, but there are people who feel that way. And if you feel really strongly about this, this isn’t going to work. If what you really want to do is have seven people become the owners, then you’ve got to do it another way.

ESOPs can be hard work. If you want to use your ESOP as a way to motivate employees to drive results and profits, then you're going to have to invest time in educating your employees about the ESOP and the business.

Once you set up your ESOP, the expectation that, “Well, now everybody’s just going to get it, and they’re all going to act like owners and everything’s going to be wonderful,” doesn’t really work that way. Like anything else in companies, if you want to achieve results, you have to work at achieving those results.

And what the research, in our experience, shows is that companies need to commit to things like setting up an internal communications committee with employees who are going to be in charge of helping explain not just how the ESOP works, but how the company works. That means, ideally—and these aren’t things you have to do, but these are things that make it work a lot better—becoming more of an open-book company, starting to share key metrics with people. And it’s not really just focused on the income statement. It’s about all the metrics at the particular work level that make that work contribute to the company’s success or not. It’s things like creating high-involvement management systems, work teams, and employee committees, and ideas teams.

If my company becomes employee-owned, should I stop offering a 401(k)?

So a number of companies do that. Most companies don’t fiddle too much with their 401(k), because taking something away from people, they might not be happy about that. ESOPs are just an add-on. But you can definitely do that. I should note, by the way, for anybody out there with a 401(k), the typical match is based on what the employee defers. But you don’t have to do it that way. In our own organization, we have a 401(k) for our staff, and everybody gets the same. Everybody gets 3 percent.

What happens if you have a bunch of employees leave one year and you have to buy them all out simultaneously? What do you need to do to be prepared to do that? How big of an issue do you think this is?

What you need to do is plan for it. And it’s not an issue much in the early years, because, first of all, you don’t have to start paying off these distributions till your acquisition loan is paid. And there’s a lot of in-the-weeds stuff here, because the loan typically goes to the company and then is re-loaned to the ESOP. And the internal loan is on a longer term, so that the shares are allocated over a longer period of time. But you can probably wait typically 10 years before you start paying people out, unless it’s because people are retiring or die or disabled. So there’s some flexibility on that.

But after the first several years, you really need to start carefully planning for this repurchase obligation and making sure that you have a really practical, solid way to pay for it. We’ve done extensive research on how many companies end up in trouble because of this. They can’t pay it, and when that happens, they typically have to sell the company. It’s a really small number where that happens. So successful companies are able to put aside the money to do this. Part of the reason that happens is, if you become a 100-percent ESOP, you don’t pay any taxes. And that’s not a loophole. It’s not something some clever lawyer figured out. It’s a law passed unanimously by the Congress in the late 90’s.

So you don’t pay any taxes. That’s a lot of money to save the deal with the repurchase obligation. And by the way, it turns out that 100-percent ESOP companies are on a real acquisition binge. Once they’ve paid off their initial debt, they start accumulating a lot of cash. And because they’re typically successful companies, they’re going and buying a lot of companies. In fact, one of the things that we’re going to start providing more resources on is for companies that say, “I really like the idea of an ESOP, but I just don’t want to do it in our own company.” You can sell to an ESOP company. There are a lot of companies looking for companies to buy, so that’s an alternative, too.

What happens if a company decides to start an ESOP, but then because of a recession, or whatever reason, the business doesn’t do as well?

So a couple of things can happen. Of course, if you have a loan, and you can’t pay off the loan, then it’s like any other situation. The creditor’s gonna say, “Okay, I need to do something about this.” And so, typically, what you see when a company runs into trouble is one of two things: If it’s really in trouble, you look for another buyer, and you get whatever you can. And the ESOP is bought out, and if there are other owners, they get bought out as well. Fortunately, that doesn’t happen very often. Obviously, it doesn’t happen never. But it’s rare.

More common is the business goes through a downturn, but it realizes it can come out of it. And so if they have enough reserves, then they can do that. If they don’t have enough reserves, then maybe if you have a seller note, then this note is renegotiated to pay it out over a longer period of time. Or maybe some of the interest is exchanged for warrants, so that the company has less debt. So you’re restructuring the debt so that the company can survive through this. In some rare cases, the seller is just forgiven some portion of the loan. But fortunately, that doesn’t happen very often.

Read Full Podcast Transcript Here

.png)