Introduction:

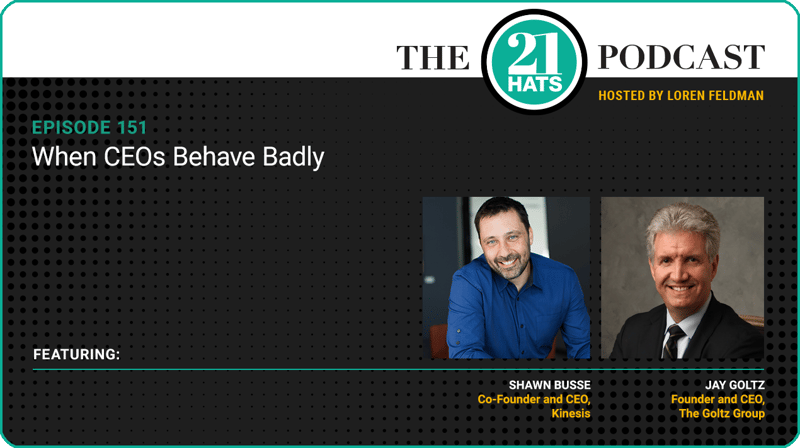

This week, our conversation starts with Shawn Busse and Jay Goltz trying to understand why CEOs keep going viral for their misguided attempts to rally the troops. Shawn suspects CEO screeds have always existed—they just haven’t been recorded. He also thinks they tend to come more from public company CEOs who are beholden to shareholders. Jay thinks they’re just morons. “I really don’t understand how someone could be smart enough to run a big company like that,” he says, “and be so completely ignorant. It’s shocking to me.” Of course, CEOs of both publicly owned companies and privately owned companies do have to do unpleasant things sometimes, but Shawn and Jay say they’ve learned from their own experiences handling layoffs and recessions. “Do we have to go out of our way to be callous about it?” Jay asks. “I don’t think so.” Plus: the very different ways Shawn and Jay manage their hiring processes. Oh, and, what would happen if Jay applied for a job at Shawn’s business?

This content was produced by 21 Hats.

See Full Show Notes By 21 Hats

Podcast Transcript

Loren Feldman:

Welcome, Shawn and Jay. It’s great to have you here. I want to start today with we seem to have had a spate lately of CEOs going viral for the wrong reasons—for talking to their employees in a way that can seem, I don’t know, a little tone deaf. In one, the CEO told her employees to stop whining about not getting a bonus and to get to work. “You can visit pity city,” she said, “but you can’t live there.” And another CEO complimented one of his employees for selling the family dog so he could return to the office. He also challenged the idea that you can be the primary caregiver for a child while also working full-time. I don’t know, my CEO friends, what are we to make of this?

Jay Goltz:

You know what? You used the word “tone deaf.” I think that’s a little weak. Just morons?

Loren Feldman:

[Laughter] Okay.

Jay Goltz:

I don’t know. Certainly, we all at times maybe have said stuff that’s tone deaf. This is so huge, their CEOs are big—and one of them makes $4.9 million, and doesn’t think about the fact they make $4.9 million a year, and they’re talking to people like that. I don’t think that falls under the category of tone deaf.

Loren Feldman:

Not just talking to people. Telling people not to complain about not getting a bonus.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, so I think that’s a little soft sell, calling that tone deaf. I think that’s just—

Loren Feldman:

Well, I wanted to start—

Jay Goltz:

You did. It was a good warm up. You put it right in the middle of the plate for me, and I’m hitting it. All right, it’s just like, wow, seriously? And my guess—I’m no expert in this. I’ve never looked into it. I’m guessing this—if you looked into the background of all these people, they’ve never been at the bottom, anywhere. That’s my guess.

They went to the right schools, and they just can’t identify with regular people. That’s my guess. I could be wrong, but I don’t know how you could grow up—or, especially in my case, start a business where I had a bunch of people not making much. I wasn’t making much more than they were in the beginning—and not empathize and understand—versus you’re making $4.9 million.

Loren Feldman:

Shawn, how did these hit you?

Shawn Busse:

I mean, I have a couple of thoughts on this. One is that I suspect these types of conversations have been happening for a long time. It’s just that now with the prevalence of Zoom, and remote meetings, and the ability to record things, just like with social media, we’re just seeing people for who they truly are, in some cases. And so it’s like, you used to be able to get away with it, I think. And now it’s harder.

And then the other thing, speaking specifically to the “pity city” CEO—or the pitiful CEO—if you watch her, she starts out pretty calm and collected. And then there’s just a moment, you see her amygdala just hijacks her. She just goes into this totally different space. And then when she finishes it, she just sort of raises her hand like she did a great thing. And I think she thinks she was motivating and rallying the troops.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, like mic drop, mic drop.

Shawn Busse:

Right, the mic drop moment. Look, if I can be empathetic for a minute, she’s running a company that does commercial office furnishings, which is probably one of the worst businesses you could be in in the last few years. And so I’m guessing she’s getting all this pressure from the market and from her board to perform. And she’s just pushing that down onto her people.

Jay Goltz:

But she still got a bonus, though. Did you notice that? She still got a huge bonus. I’m having a hard time trying to be empathetic to her. But I’m having a hard time understanding. Like I said, you know, maybe we’ve all said things that were—maybe it’s just me. I’m sure I’ve said things that have been tone deaf, but this is so beyond that. I just say to myself: How could you be that ignorant, and not at least, as a leader, say, “Listen, I know it’s upsetting that you’re not getting your bonuses”? It’s like, “How dare you ask?” And it’s really remarkable. I don’t know. And I’m sure, to Shawn’s point, this has been going on for years. This isn’t a new thing.

Shawn Busse:

And I think two things can be true at once. One is, I think leaders are under a lot of stress, and have been under a lot of stress across all industries. And also, I think she’s a terrible leader. I think they’re both true. I mean, everything about that—the lack of empathy, the size of compensation she gets in relationship to the other people, pushing down on people, motivating through fear and threats. I mean, it is text book terrible leadership. Honestly, I don’t think she’ll survive this. I think she’s out. I might be wrong, but I just don’t know how the company goes forward with that kind of behavior. I mean, they’ve got to do something.

Jay Goltz:

My daughter-in-law is a labor attorney, and she just went off on her own, and she’s doing a seminar today. And she’s speaking about the intelligent way to do layoffs—in the last two weeks, there have been some horrendous examples of it—and I said to her, “You know what? You’re really doing three things.”

First, as a lawyer, you have to explain the legal things about it. Okay, fair enough. Then you’ve got to think about brand. Your company’s going to be known for this. How do you look if you go and lay off a bunch of people and are cold about it and don’t do it in the proper way? Then you need to think about if you’re going to be calling people back.

This is a true statement I’m gonna tell you: I’ve done speeches to hundreds of people. I have never met one, when I say, “Do you know how unemployment works in your state?” No one really understands it who I’ve talked to. I’m sure there’s someone somewhere. They’ve guessed at it, and I go, “No, that’s not how it works.”

The reality is, in Illinois, if somebody is making more than, like, 50 grand, it’s probably gonna cost like $27,000 of unemployment. You don’t get a bill from Illinois. It throws into your rate, and it slowly comes out of your thing for the next three years. But most entrepreneurs don’t know what their unemployment rate is. So it’s expensive to lay a lot of people off.

So the point is, if you’re thinking you might have to bring them back in four or five months, you know what? You just paid $27,000 out, and now you’re going to bring them back. So you should consider that. Maybe there are furloughs, maybe there are other things you do. And then, lastly, it gets to another level of: Do you want to be a decent human being? I mean, this is disturbing to people. Forget about the brand. Forget about the money. How about trying to be a decent human being and recognize people are traumatized by that sometimes, and try to be nice? How about that?

Loren Feldman:

There are some interesting issues in that, Jay, and things have changed because of the pandemic and Zoom. Wasn’t it McDonald’s recently that told people not to come into the office so they could be laid off on Zoom? They wanted everybody to be at home. And that was an interesting question. Some people took the side that that is the humane way to do it. Let people be at home and not in the office.

Jay Goltz:

That’s funny you say that. My nephew just took a job there, a pretty decent job there. And he told me he wasn’t sure if he was getting laid off or not. And I understand that running a corporation with tens of thousands of people is different than running it with 50 or 100. But there probably is an argument as to what’s the most humane way to do it. What, are we supposed to have a meeting with 10,000 people? I’m not at all saying, “Oh, no, it’s got to be one-on-one in person.” Maybe it can’t be. I understand that. But there are still ways of doing it that are decent and humane as much as you can be. I mean, some people are just gonna be upset. I got it. But do we have to go out of our way to be callous about it? I don’t think so.

Shawn Busse:

Jay, I’m curious, in your career, have you had to lay people off for financial reasons?

Jay Goltz:

Listen, I’ve lived through, what, five recessions, six recessions, in 45 years? Probably, a couple of times. Like the bad one, 2008, I cut everybody back to 32 hours. We were doing furloughs, and I didn’t lay anyone off. If there was someone who was marginal or who was just barely holding on, and we just hired them, yeah, sure, I would lay them off because it, but I’ve never—

Loren Feldman:

So you did lay some people off.

Jay Goltz:

Very minimally, though, very minimally. And all these years, maybe three people, I don’t remember. I’ve never laid off like five people or something. And if somebody was barely holding on to the job, it’s like, at that point, it’s not fair to the ones who have been there for years. You have to balance out. You know, furloughing ain’t great either and cutting hours isn’t great either. So there is a reality to, you can only cut people’s salaries so much to where they can’t put food on the table. So can you cut people from 40 hours to 36? Yeah, probably, but you can’t cut them to 25. Now, people do that, but it’s just a mess. And I’m not doing that.

And you know, I’ve read this once. Somebody once said, “Any company that lays off people is an indictment of management.” I think that’s a ridiculous statement. It happens. It happens. I’m sure sometimes it’s done in an irresponsible way, for sure. But, you know, the pandemic, all the high-tech companies are doing so well, they hired a bunch of people. Oops! I mean, who knew it was going to drop off? I mean, layoffs happen. Not here so much, but other places.

Loren Feldman:

How about you, Shawn? Have you had to do it?

Shawn Busse:

Yeah, let’s see, how many recessions have I survived? So I started in 2000, that was a recession; we had 9/11, that was kind of a mini-recession; 2008; and then the pandemic, which behaved differently than a recession, but kind of has similarities. So three, four, and 2008 wiped me out, like totally wiped me out. And it didn’t hit me until late in 2009, and I was at a point in my career where I honestly was still trying to figure out how to run a business. And I just didn’t have a good business model. That was really important learning for me.

And we just got wiped out. All our customers stopped buying, kind of all at the same time. And so we had to pretty much lay everybody off, including myself. You know, if there had been any jobs in the market, I probably would have taken it and had just become an employee, at least for a little while. But yeah, that was rough. That was really emotionally very hard.

Jay Goltz:

How long did that go on?

Shawn Busse:

You know, that’s the funny part about it. As I looked back at it recently… because it felt like forever. It felt like: Wow, we were really suffering for a long time. And the truth was, the momentum was building, probably within eight-nine months of that low point. And then within a year, we were rockin’ and rollin’ again.

Jay Goltz:

Wow. I mean, the reality is, you’ve got to keep the business in business. The worst recessions? Like I said, I’ve been through, I don’t know, six or seven. Did my business ever drop off 20 percent? Yeah, in 2008 it did. But by cutting back the salaries and doing some furloughs, we squeaked through. It’s difficult, but I see some of that with the last two you mentioned doing these things. And I really don’t understand how someone could be smart enough to run a big company like that and be so completely ignorant. It’s shocking to me.

Shawn Busse:

Well, you have a superpower or secret weapon that these publicly traded companies don’t have, which is, you are beholden to yourself and your employees. They are beholden to Wall Street and shareholders. So, once profits fall below a certain level, they have no choice but to eviscerate the company. And you can choose to take less compensation, you can choose to reduce wages, you can ask people to sacrifice. I mean, that’s why I’m so passionate about owner-run businesses. It’s because they can actually be human. I don’t think that MillerKnoll CEO had any choice, to some degree, except to do crappy things. And being a crappy person and being forced to do crappy things is a pretty bad combination.

Jay Goltz:

You know what, you bring up a fair point. I don’t know what it’s like to have to answer to shareholders and stuff. And I call it “selling your soul.” I’d like to keep my soul. So that’s why I run my own business. I can do what I want. But you’re right. I’m not even criticizing him. I just say: I don’t understand it.

But that’s kind of it. Now that I’m thinking about it, though: Okay, maybe they had to lay people off. No problem. They don’t have to be jerks about it, though, saying, “Stop being a pity party.” Jeez, I mean really? That didn’t save any money. That didn’t help the shareholders any. I mean, what’s that about? That was just like a flagrant foul for no reason.

Loren Feldman:

Shawn, when you had to lay people off, did you feel like you handled it as well as you could? Or did you learn from the experience? How do you look back on that?

Shawn Busse:

I was really kind of a baby business owner at the time, and we were very small. So maybe there were like four or five of us, total. And you know, I’d never had to do that kind of thing before, and I had never had any guidance on it. I didn’t have any mentors. So it was just really emotional. I felt like a complete failure. Just to be completely candid. I was breaking down in front of my employees. I just felt like such a loser. And with the benefit of time, I’ve become a lot more easy on myself. But in the moment, yeah, I felt like I was just such a disappointment. It taught me some good lessons.

Jay Goltz:

I had a really interesting meeting in 2008, when it really got bad. I sat there with, I believe, four other people. And I said, “Look, we’ll cut the salaries by X amount, and then the hourly, but I’ve gotta tell you: if we cut the hourly any more than this, they’re gonna have a hard time putting food on the table.” And one of the people around the table, who was young at the time, said either—I don’t remember which it was—“That’s not my problem,” or, “I don’t care.” And it kind of sucked the air out of the room. And that person is still here, and is doing a very good job, and I wrote that off to being young or whatever. But like, I’ve gotta tell you, I still remember it 15 years later, because it was just like… wow.

Shawn Busse:

Yeah. So actually, Loren, what changed, I’d say, in the early pandemic, I was convinced we were going to go into an economic ice age. I saw no path forward that was going to be positive for us, or a lot of businesses. Because you’ve got to remember, this is before PPP. This is before vaccines. And so I was looking at the landscape and was like, “Holy crap, this is going to make 2008 look like a freaking walk in the park.”

And so what we did, which was so different than 2008, is we went into action mode right away. And we put together a plan. And the plan was all about getting really close to customers, being empathetic with customers, and supporting them. We offered many customers, like, “Hey, you don’t have to pay us if you don’t have the money. Like we literally will keep working for you. If you can’t pay us, it’s okay. We want to help you.” And the goodwill that that bought was amazing.

And the other thing we did is we built a huge spreadsheet that showed, “Okay, phase one is senior leadership”—because now we’re bigger, right? We’re a lot bigger than we were in 2008. So we could take the hits. We had cash reserves. We were making good wages, unlike we were in 2008. So I was like, “Okay, phase one, senior leadership takes a pay cut of this much. Phase two, senior leadership takes another pay cut. Phase three, middle folks take this pay cut. Phase four, the lower-paid people take a small cut.” So it was really this tiered program. And we shared it with the whole team. We were totally transparent about it. “This is what we’re going to do. And our goal here is to extend the runway in hopes that something good happens.”

And as it turned out, a lot of good things happened, in terms of the government not treating it like they did in 2008, which was to just basically let everybody twist in the wind. So the combination of PPP gave customers confidence to keep going. The goodwill we had built, the better business model we had built, all those things in combination made it so that we actually didn’t suffer at all. And then by the end of 2020, we had our best year on record—best year: record profits, record revenues. And I really think that those first months made a huge difference, because it demonstrated to the team that we, as the leaders, were willing to sacrifice long before we asked them to sacrifice. And I think that’s why we had such good retention throughout the pandemic while everybody else was having tons of turnover.

Whereas, if you contrast it with other companies, as soon as things got rough, what did they do? They laid their people off. And then they realized—to Jay’s point—“Oh shit, we need those people back.” And then they tried to hire them back, and they’re like, “Fuck you.” And then they couldn’t find people. So I think that there’s a big difference in how you treat adversity, whether you do like our pity city CEO did, or you actually work together. So that was my lesson.

Jay Goltz:

I mean, the fact is, the first thing you should do is not knee-jerk. I mean, the second you fire them, like I said, you’re just paying an annuity. You’re gonna pay it in unemployment for the next three years. So you should think about, maybe it’s worth carrying it for a little bit, because it’s not free to lay people off.

Loren Feldman:

It’s not just unemployment. I mean, a lot of companies pay severance as well.

Jay Goltz:

Right.

Shawn Busse:

And recruiting fees. So then when they need people back, they pay recruiters all this money to go get new [people]. It’s so expensive. It’s crazy.

Loren Feldman:

It’s spending a lot of money to do damage to your brand.

Shawn Busse:

Right.

Jay Goltz:

The more I’m thinking about it, you’re right, Shawn. We don’t know what they have to deal with. Okay, that’s clearly part of it. They have to deal with stockholders. But I really think the other strong part of it is, they didn’t work their way up from the mailroom. They just didn’t, most of them. They went to Stanford or something, and they got recruited, and they got put into these [positions]—they really don’t empathize.

And I think the way they’re talking to these people about, “Get over the pity party.” This is what they say to themselves. I mean, they’re very successful. They probably have a strong work ethic. And they’ve got persistence. And that’s how they want someone to talk to them. And they go, “Yeah, you’re right.” They’re not talking to themselves. They’re talking to someone who’s making $43,000 a year and is trying to make their car payment. They just can’t identify with what the real world is about, it seems to me, and that is not what the typical small business owner is at all.

Shawn Busse:

Yeah, it’s a really different universe. When we wrote the book, talking about how to do marketing in an owner-run business, a lot of it is contrasting corporate America and what’s called shareholder primacy, which is where the shareholders are the customer. They’re the primary customer—meaning in a public company, it’s the stock market. And in a privately held business, you can pay attention to lots of different constituents, including your employees, including your community, including the environment—you know, on and on and on and on. So I think it’s just a systemic problem that is really hard to get around. I don’t really know what the answer is to it. But I know I don’t want to be part of it.

Loren Feldman:

You know, the second company that we referred to was Clearlink, a digital marketing firm. That’s the CEO who complimented his employee for selling his dog. I don’t think that’s a public company. I’m not sure.

Jay Goltz:

They probably got private equity, though. Probably.

Shawn Busse:

That would be interesting to see. I mean, you can be a jerk and be a privately held company.

Loren Feldman:

That’s kind of my point.

Read Full Podcast Transcript Here

.png)