Introduction:

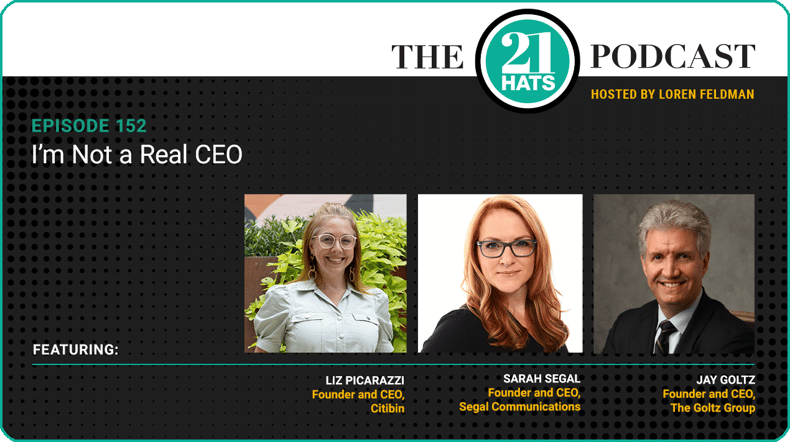

This week, Jay Goltz, Liz Picarazzi, and Sarah Segal talk about the inherent conflicts between being an entrepreneur and being a CEO—and the different skill-sets each role requires. Does it make sense for the same person to do both jobs? Is being CEO even a full-time job? And when does it make sense to replace yourself as CEO? Liz says she’s thought about it. Jay, not so much: “Could I have found somebody 10, 15, 20 years ago who was a better manager? Sure. But it just wasn’t worth it.” Why not? “It’s gonna cost you $250,000 a year,” Jay says. “Is it worth paying that?” Plus: Liz and Sarah talk about positioning a company to be acquired. And Sarah proposes a PR campaign for Liz’s package bins right on the spot.

This content was produced by 21 Hats.

See Full Show Notes By 21 Hats

Podcast Transcript

Welcome Jay, Liz, and Sarah. I appreciate your taking the time to be here. I want to start today with a blog post that Jason Fried, the founder and CEO of 37signals—also known as Basecamp—recently published. In it, Jason, who’s been a guest on this podcast, made some interesting assertions. One is that you really can’t be both a CEO and a founder.

Why not? These are his words: “Because the founder’s job is injecting risk into the business. It’s flooding it with new ideas, stuff that seems hard to do, ideas that no one else would dare try, placing the kinds of bets that only someone who started the damn thing would be willing to wager. … A CEO’s job, just about the opposite. It’s reducing risk, executing diligently to achieve obvious goals, staying in business at all costs.”

You guys are all CEOs and founders. So I’m kind of wondering what you think about this. How about you, Liz?

Liz Picarazzi:

So I found this article incredibly relatable. I definitely am more of a founder—even though I’m also the CEO. For me, the distinction between founder and CEO has only become really apparent in the last couple of years as we’ve grown, because I really like being the founder. I like to be the innovator, the creator, the one who’s injecting risk, the one who’s making bets, the one who’s cycling ideas. That’s my sweet spot. That’s what I enjoy. That’s why I am an entrepreneur.

So the more I’m called upon to be a CEO—and I’ll admit, like Jason, it’s not a full-time job for me to be the CEO. I already know that I prefer the former. And reading articles like this is actually very helpful, because I sometimes feel bad that I’m not a better CEO. And it makes me understand why the skills and what you bring to it are very different. The roles are very different. Having a real CEO—because I’ll call myself not a real CEO—is probably in our near future. But I understand myself better by reading that article. I guess I’ll just put it that way.

Loren Feldman:

Sarah, how about you? How did you react?

Sarah Segal:

Well, first of all, if you’re a big enough company, to have the luxury of having a founder and a CEO, like, have at it. Do a division of labor. But most small companies—as the name of your podcast—you’re wearing 21 hats. You’re CEO, you’re CFO, you’re founder, you’re the person who takes the garbage out at the end of the week. You do it all.

I also think of it as like saying that somebody is only left brain or right brain. I ask that question a lot when I interview people for jobs. I’m like, “Well do you consider yourself a creative or somebody who’s more of an analytical thinker, more scientific, etc.?” And most everybody sees themselves as kind of a mesh between the two. But I think you can be founder and CEO. I think that if you’re a founder, and you don’t have some CEO abilities, you’re gonna fail before you start. Because you can’t just always throw caution to the wind.

If you have a staff, you have to make payroll. You can’t buy that fancy new office that you want to buy, just because you think it would be better optics for your clients. You have to have some of those qualities, even if you are a reckless, enthusiastic founder. You still have to have that. But as a CEO, you also have to take an amount of risk. Like, “Do I want to get a small business loan so I can invest in my company? Where am I gonna spend that money?” There’s a risk of taking out a loan, especially as a small business owner, because usually it’s not just based on your business. It’s based on your personal credit.

Loren Feldman:

And the collateral that you put up.

Sarah Segal:

Exactly. So it’s like, I agree with the statement, but I don’t think it’s applicable to every business because of their size, essentially.

Loren Feldman:

Jay, I just sense that you’ve got something to say about this.

Jay Goltz:

I would say this: Jason Fried’s a very smart guy, and he’s been very successful, and that’s his opinion, but I think it’s a false choice. I understand, I fully agree with both Liz and Sarah. It can be a struggle—and I really would replace the word “founder” with “entrepreneur.” I think that’s more accurate.

Loren Feldman:

I think you both mean very much the same thing.

Jay Goltz:

Yes, yes. I’ve said many times, “I’m 80 percent entrepreneur and 20 percent manager,” and can it be a struggle? Yes. But to suggest that the two of them are complete polar opposites? I’ll just say, from my perspective, it’s just ridiculous to suggest that, “Oh, you’ve got to be conservative and your number one thing should be not going out of business.” Yeah, I do think that should be your number one thing. So that means that entrepreneurs shouldn’t worry about putting themselves out of business?

There’s somewhere between just being that reckless, do-whatever-you-want, and bet-the-farm thing, and not taking any chances. I think that’s a false choice. You can be a CEO and still take chances. Do I not take chances that could put me out of business? Yeah, I’m crazy like that. I don’t really want to put myself out of the business. When I opened up the store in New York, I did a pop-up. I did it for seven months, knowing if it didn’t work out, I wasn’t going to be stuck with a $500,000-a-year lease or something. So I believe it’s a false choice. I believe you can do both.

The tone of his comments are like: The founder/entrepreneurs just go and do crazy stuff, and it might put them out of business, and then the CEO can’t do anything that’s not conservative. It’s just a ridiculous summary of it. I live in that world. I take chances all the time. But yes, I am cognizant that I shouldn’t go bet the ranch, because why would I do that, at this point? I’ve got 130 people who make their living here. Why in the world would I want to bet the ranch to go ahead and grow it any more?

So I don’t even know if “struggle” is the right word. Is it something you have to get a handle on? Is it something where maybe somebody would be better off being the CEO? Sure. So I fully agree with everything both Sarah and Liz said, but I don’t think it’s one or the other. And I absolutely do not agree that, “Oh, you can’t both be the founder entrepreneur and the CEO at the same time.” That’s just…

Sarah Segal:

It’s about taking calculated risks.

Jay Goltz:

Right, right.

Sarah Segal:

That’s the meshing of the two. You can take a risk, but it has to be thoughtful, and you have to know what the consequences are, and you have to have an out. Doing a pop-up is a great example for a retail company. You test the market before you dive in head-first. I think even a founder or an entrepreneur would do that.

Jay Goltz:

I mean, he’s suggesting that if you don’t stay wild and crazy and take wild risks that you’re not going to be successful. That’s just ridiculous. I mean, maybe in his world, it is. Maybe in his world what he said is accurate. But there are millions of companies out there that have managed to transition from being a startup entrepreneur to running the company.

And is it maybe hard for some people? Sure, I get it. It’s a different skill-set. But I absolutely don’t think that it’s one or the other. And I’m living proof of: I’m still very entrepreneurial. Have I toned it down over the years? Yeah, because I got the business big enough now. I just need more money less than I need more risk. So have I gotten more conservative? Yeah, absolutely. But I certainly haven’t become conservative to where I just don’t take any risks. Me and everyone else out there, it’s not just me. Every other business that’s out there is in this similar situation.

Loren Feldman:

What are you thinking of, when you say that you still take risks?

Jay Goltz:

At this point, here’s my new word: It’s not about balance, it’s about alignment. I don’t need to grow the business a lot more. I want to grow organically. I’m not opening more stores. Why would I open another store? It’s more people, more exposure. I don’t need to.

Loren Feldman:

Right. But you said you’re still taking risks.

Jay Goltz:

I take risks with advertising. I certainly still borrow money. I take risks with trying new product lines and doing stuff. So it’s not like I’m petrified of taking any risks. I just don’t need to take the risks anymore because I got the business big enough that I’m making a really good living and everybody’s happy. And this is where I say: “It’s not the income. It’s the outcome.”

I got out of the fast lane. Now I’m in the medium lane. I don’t need to do it anymore. I got it big enough. My company—and I’m not exaggerating—is 50 times bigger than I ever thought it would be. I never had any grand plan for what it turned into. I’m surprised myself as to how big it got. It’s big enough. There is such a thing. It’s big enough. I’m happy.

Sarah Segal:

That’s really interesting. I went to an event with a staffer who we had, and she looked at me afterwards—we were having drinks—and she’s like, “What is your grand plan for your business? Where do you see the company in 5, 10 years, or whatever?” And I’m curious, Jay, it sounds like you’d never had that grand plan.

Jay Goltz:

No.

Sarah Segal:

Liz, do you have that grand plan?

Liz Picarazzi:

No.

Sarah Segal:

So I don’t either.

Jay Goltz:

So I’m saying to you, Sarah, let’s say you get the business up to—and I assume in PR world, a $6 million business would be a nice-sized PR firm?

Sarah Segal:

Yeah, that’d be a nice size.

Jay Goltz:

Okay, so you wake up one day, and you’ve got a $6 million PR firm. You’ve got happy people. You’ve got happy customers. You’ve got happy employees who are making a lot of money. There’s nothing you can’t buy, within reason. You might say, “Yeah, I don’t think I need to push it like I used to, because what’s the point?”

Sarah Segal:

Well, I do live in San Francisco. Things are expensive here.

Jay Goltz:

So then say $10 million. But at some point, you have to wake up one day and go, “Why am I doing this? And like, why would I want more exposure? It’s all fine.” What I just said to you, I wouldn’t have said 10 years ago. No way.

Sarah Segal:

Yeah, it’s not about the money. It’s more about the legacy. I would like the company to live on beyond me. That’s kind of my goal. I feel like I’ve created a company with a good vibe, a good purpose, a place where people like to work, where people stay, that promotes education and does great work for its clients. And I would like someone to want to continue that purpose. It’s not about another paycheck, another paycheck. So I’d rather reinvest that money into building something that can live on in perpetuity.

Jay Goltz:

Which I think is great. And I certainly want to do that. The only line I would draw is, in my case, I’m going to try to do that. But I am not going to hook my happiness wagon to that. Because if I can’t pull it off, for whatever reason, I gave it a shot. I am not going to make myself crazy trying to figure it out. I’m doing everything I can to do that. But I think we have enough responsibility when we’re alive to do it than worrying about when we’re dead, what’s going to happen. I just don’t want to hang that on anybody. And I know companies do, but I’m not buying into that.

Loren Feldman:

I’d like to go back to something Liz said before. Liz, I’m curious, having heard what Jay just said about how one person can embody both roles, does that affect your thinking at all, in terms of what you said about not being a real CEO and thinking that your business might need one?

Liz Picarazzi:

Well, I would say that, because I am still a good CEO, maybe not a great one, it does temper my more impulsive tendencies as a founder.

Sarah Segal:

Why do you say you’re a good one, and not a great one, just to clarify that?

Liz Picarazzi:

I think that the structure of being a CEO, and the focus more on execution, is just not my strength. I’m much more creative. I like working in the area of new ideas. I’ll implement them for a while, but then I’ll be really eager to pass it off and move on to the next.

Sarah Segal:

Do you think somebody else could do a better job than you? For real?

Liz Picarazzi:

Honestly, I have to say that thought crosses my mind quite a bit.

Jay Goltz:

I have an answer to that. How about this—because this is what I’ve lived in—yes, you could absolutely find someone better. It wouldn’t be worth the money. It would suck the profit out of the company. Could you go hire someone who’s super smart to be a great [CEO]? Yeah, sure. It’s gonna cost you $250,000 a year. Is it worth paying that? No, because you’re doing it good enough.

I mean, could I have found somebody 10, 15, 20 years ago who was a better manager? Sure, but it just wasn’t worth it. And I would say, in your case, you’re still very young. You haven’t been doing it that long. The reason you’re not a, quote-unquote, great CEO is you’re still in training. I mean, it takes years to figure it out. Most CEOs—if they’re not in the computer industry—are 50, 60 years old, because it takes 20, 30 years to get all the skill-sets you need to do it properly.

Loren Feldman:

And there’s one other factor, which is, you did bring in someone who kind of complements your skills. That someone happens to be your husband.

Liz Picarazzi:

Yeah, absolutely. So I have been able to spend more time as founder since he came in as COO. And I mean, that has been helpful in not only filling gaps, but in just strategically being able to talk to him about literally everything in the business, and being able to get input that is based on his knowledge and what he’s doing hands on. But also that he’s going to have the right motivation on decisions, because we own the company together.

So that really was a big relief. I do sometimes worry about what would have happened had he not come in, and we grew as we did. Because just everything with operations, before he came in, was not very good.

Jay Goltz:

I can tell you, you would have found somebody who would have worked out fine. And just because they’re not your husband doesn’t mean… I’ve got 20 people who care what we do every day. They don’t need to be my relative to care a lot. So you would have found somebody—maybe not as good, but you would have found somebody. That’s the answer. I mean, you didn’t need to because he was there. And that’s good.

Liz Picarazzi:

Yeah.

Loren Feldman:

Jay, I want to go back to you on one point. You have made that point here before about being 80 percent entrepreneur and 20 percent manager. I’ve never really bought that. I think anybody who listens to this podcast has heard that you’re very thoughtful about management issues.

Jay Goltz:

Okay, I can clarify that. No, no, I’ll tell you what it is, because there is something there. You’re right. I think I have good management skills. I think my weak spot that I have to continually work on is paying attention to looking at reports. I have to discipline myself to sit down and play manager and look at the reports and follow up and have meetings. And that’s not my skill-set.

So yes, you’re right. I’ve got some good skills in it. But my head is usually thinking about—lookit, I’m doing the podcast today. Should I be doing the podcast today? Or should I be going through my inventory and figuring out what we need to get rid of? I mean, I get distracted easily. And I like—this is really the issue—the entrepreneurship side. I like figuring stuff out. I like building new things. And I have to discipline myself to go, “Okay, you built enough new stuff. Pay attention to your inventory problem.” It’s a constant struggle. It is. That’s where the 80/20 comes in. So maybe it’s 50/50. Yeah, you’re right, it’s not 80/20. It’s probably 50/50.

Loren Feldman:

Do you worry about finding your job less rewarding as you go on, as the need for you to focus more on management and less on entrepreneurship continues?

Jay Goltz:

No, I gotta tell you, what’s interesting lately. I just turned 67. My friends are between 65 and 72, and the ones who are quote-unquote professionals—doctors, lawyers, stockbrokers—they’ve got some real issues. Dentists. You know, dentistry is physically demanding.

I am thrilled that I own a business, because there’s nothing about my job, quote-unquote, that’s a problem. Those guys are retiring because they don’t want to deal with it anymore. And I respect and understand it. The pressure of having the client calling you, the pressure of being a dentist, the pressure of being a doctor, dealing with hospitals. They at some point go, “Yeah, I don’t want to deal with this anymore.” I don’t have anything in my life going to work that I think, “Oh my god, I’ve had enough of that.” I come to work. No one’s looking for me. My life is 180 degrees from where it was 30 years ago. There’s no post-it notes. There’s no phone messages. There’s no, “Oh, Jay, I’ve gotta talk to you.” If I didn’t show up for two days, most people wouldn’t even notice it. So I’ve managed to pull that off.

Loren Feldman:

Without getting bored?

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, lookit, I’m doing the podcast. Why do you think I do the podcast? I like doing the podcast. I do what I want to do.

Loren Feldman:

I’m glad. I appreciate that.

Jay Goltz:

No, I do. I like doing it. I like talking business. That’s my hobby. Yeah, I’ve got nothing that’s going to make me think, “Oh, no, you can’t do this much longer.”

Loren Feldman:

The last thing on this blog post that I want to mention is, Jason Fried also says that being a CEO really is a part-time job. Let me quote him: “There simply aren’t that many big picture things or decisions to execute day in and day out, or even week in and week out, to make it a true full-time job. A role? Yes. A hat to wear? Yes. A full-time job at a smallish company? No, it’s part-time at best, quarter time even better.” Any thoughts on that?

Jay Goltz:

Okay, maybe, maybe. You know what, if you said, “Jay, you can only work 20 hours a week.” Yeah, sure. I might agree with him on that part. If you’ve got the right people in place, you’re overseeing. You’re not managing. I could go with that part. Maybe it isn’t a full-time job.

Loren Feldman:

Sarah?

Sarah Segal:

Yeah, if you’re already set up. If you’re set up, and you have the wheels turning and the gears are clicking into place in the right place, yeah, it should just be on autopilot. And your decision-making should be relatively minimal. And you should be spending your time selling and being a representative of the company, for sure.

Jay Goltz:

Or doing a podcast.

Sarah Segal:

Or doing a podcast. [Laughter]

Loren Feldman:

Liz, how about you? Does that part-time job thing make sense to you?

Liz Picarazzi:

It does. I sometimes think if we—as I sometimes want to—double, triple, quadruple as we grow, that’s when I think I’m really not going to be a good CEO. And I probably wouldn’t enjoy that job. I’d like to be alongside of it. But growing a fast-growing company as that CEO, I don’t know. I don’t think I would like that.

Jay Goltz:

What I’ve been telling you is, if you have the right key people in place, it’s not a problem. You know, I always say: They don’t take a bullet for me, but they take the bullshit for me. Like, they’re doing everything. Here’s part of the key, though: You’ve got to be big enough to pay enough. If your business gets big enough where you can start to pay some six-figure salaries, you’re gonna get some very responsible, smart people. They can take that off your responsibilities. So you’re not big enough to be at that point yet. If you had a few other more senior people there, I’m telling you that your life would be much easier. But you’re not there yet. You’re growing into it.

Loren Feldman:

All right. I wanted to talk about something, Liz, that you’ve brought up previously on the show, which is your thoughts about developing strategic partnerships with other companies. Have you made any progress with that?

Liz Picarazzi:

Yeah, there are a couple of areas for the business that are really interesting, and I’m really engaged with, where talking to a potential vendor starts to sound not like I’m buying, let’s say, a piece of hardware from them, but rather there could be some sort of a partnership, which then in my mind goes to potential acquisition, like 10 years down the line. And so I’m noticing in various places—you know, one of them is having to do with components for our bins. But another one is, we’ve had a lot of requests to put advertising on the bins. So I’m starting to learn about advertising on public fixtures, so I’m looking at how bus stops have ads on them, or benches, or other types of trash receptacles.

And so for that, too, it’s like, “Okay, I’m talking to a couple of companies on this.” And I feel like, is this a sort of a transaction where I’m enabling my customers to purchase their bins via advertising? And is that something where it’s kind of transactional or partnership? But the exciting thing is that I do see that some of the companies that I’m talking to could take us into a place that we wouldn’t have even thought we were in a couple of years ago. Like, I wouldn’t have anticipated putting ads on the bins, working suddenly with media companies and with brands.

That sort of partnership I’m really excited about. But also, I guess I’d say I’m in a place of learning a lot now and I really like being in that place. But I feel like, how much can I learn and figure this out before I actually make a move? So it’s almost like I’m sniffing, and me and these other companies are kind of sniffing each other out. And I do get attached to: What could that partnership look like? And I need to remind myself it can proceed more organically.

Jay Goltz:

My only comment with that is: That all sounds great. Whatever you do, I can’t emphasize enough, I’d make sure that there’s an out, because you just don’t know what’s going to happen. Whatever deal you cut, I would make sure there’s some honeymoon period that if you wake up and go, “Yikes, this isn’t going like I thought,” you can get out of it. Because who needs to screw their business up?

One of the goals of the CEO should be to never get in a lawsuit. Trust me. I mean, there’s no winning in it. And I don’t think that should be a problem. I think you should be able to put together some kind of deal that you have an out after, whatever, 12 months, or something. Because who needs to get locked into something that’s not working.

Read Full Podcast Transcript Here

.png)