Introduction:

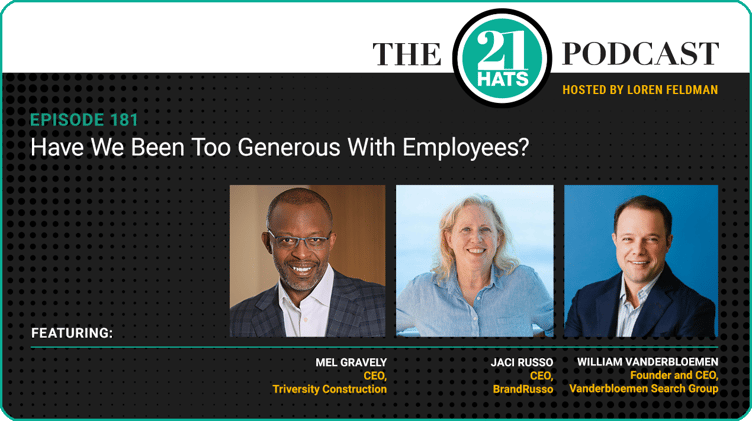

This week, Mel Gravely, Jaci Russo, and William Vanderbloemen talk about the possibility that, after several years of the Great Resignation and the labor shortage, some owners may have given away the store. We all know the risks of not offering employees enough. What are the risks of offering too much? How do you even know when you’ve crossed the line? The owners also discuss why this might be a good time to consider acquiring other businesses. “I think this is a time to double-down,” says Mel. And Jaci explains how she and her team are reviewing everything the company does to see if AI can be employed to improve each and every process. Oh, and one last thing: How exactly, in this day and age, are business owners supposed to keep track of all of the subscriptions—and all of the subscription log-ins—that they and their employees have acquired through the years? How much money are they spending on stuff they no longer use? “Thanks a lot,” responds Mel. “I’m starting to sweat.”

— Loren Feldman

This content was produced by 21 Hats.

See Full Show Notes By 21 Hats

Podcast Transcript

Loren Feldman:

Welcome, Mel, Jaci, and William. It’s great to have you here. In our email exchanges this week, Jaci, you raised an intriguing question. I don’t want to put words in your mouth. But what I read into your question was this: We’ve been through this really interesting period, a challenging time with the pandemic, the Great Resignation, the labor shortage—which I’m not sure is completely over yet. But in trying to build a culture and a business through all of that, one that attracts and retains employees, how do you know if you’ve gone too far? Is that a fair reading of the question you were raising?

Jaci Russo:

That is a very fair reading. And I would add to that, I’m in Lafayette, Louisiana. From a salary perspective, we skew lower than national averages—even state averages. And so, is it enough to meet the state average? Do I need to get all the way to the national average? Where is the line for fair and equitable these days? And am I building the culture or being taken advantage of?

Loren Feldman:

Is this primarily an issue of the pay, the dollars, or is it all of the above?

Jaci Russo:

I think it’s all of the above. We’ve always had a flexible schedule, from when we started in 2001. You could work from home or work from the office. And it’s about being a mature adult and knowing what you needed and taking care of it. So there were very few rules around that. We moved into COVID, and so that became even more so. We’ve always had unlimited paid time off. And really, 23 years in, it’s worked very well. I can think of one time when I felt like that was maybe a little bit taken advantage of.

But so, then coming through COVID, we’ve now added to that a four-day work week, pretty impressive increases in pay, a paid professional development trainer who comes to us once a month, paid one-on-one coaching. And so I’m thinking, am I adding more stuff? Have I added too much? When do I know that I’ve reached the line?

Loren Feldman:

Did something trigger this thought?

Jaci Russo:

I think that I can attribute part of my success to the fact that I’m always asking the questions: Am I doing enough? How can I do more? Where’s the right balance?

Loren Feldman:

But now, it’s: Am I doing too much?

Jaci Russo:

Right now, that is the question. Have I reached the sweet spot? Or have I gone too far past the sweet spot? So, nothing’s wrong. I just sat down and analyzed the numbers from last year. And everybody did their salary wishes—you know, “This is what I would love to be making.” And I’m thinking: If I can’t afford it, do I push to it? If I can’t afford it, do I find a way to push to it? Where’s the line?

Mel Gravely:

Interesting.

Loren Feldman:

Mel, William, have either of you thought along these lines at all?

William Vanderbloemen:

Oh, that’s the tension I think everybody that I’m working with is facing. So I don’t know if it’s helpful, or if it’s discouraging, but I would say, Jaci, that you shouldn’t feel alone. And I think particularly what we’re seeing is—as we deal with the reality that hybrid is probably here to stay, some kind of remote work, and also the tension that there’s a whole lot of productivity that happens with people in the office—I think the dilemma that I sense business owners facing is: if I’m going to ask people to be in the office, it better be the best office ever. And it better be someplace people want to come. So they focus on building culture, and they raise pay, and then they put in the Ms. Pac-Man machine or whatever the thing is that makes people feel like it’s fun. And then it’s like: When is it too much?

And I’m a huge proponent of Millennials, Gen Z, and now Gen A. I’m very bullish on our future with them. But there is that common perception I’ve heard for years that, “Well, they’re entitled.” Now, maybe that’s because they got a participation trophy for everything ever. They got titles way before they should have. But I do think it becomes a bit of a black hole. The more you feed this into the culture—“Here’s something I’m entitled to”—the more it becomes a problem. Man, I wish I had the magic formula to tell you how to figure out how far is too far, but you are not alone. And that is the tension I hear a lot of leaders managing right now.

I will say, looking at jobs reports, unemployment rates, all the things that have been a wreck since the Great Resignation—I think that’s over now. And the pendulum, which had swung hard toward the employees holding most of the leverage in negotiations, is swinging back toward employers. It’s not as easy to go get a job as it was. So that may mean that you don’t have to pour as much into culture. And then, having said that, the longer you can keep somebody and not have to hire me as a search firm, the better off you are. And if spending some on culture keeps people a little longer, then I think retention and the value creation of retention is what I hear business leaders wrestling with as they manage this tension. Does that make sense?

Jaci Russo:

It makes perfect sense. And I loved what you said about getting them back into the office. We just invested heavily into taking what was a pretty cool ad agency office vibe—we have both Ms. Pac-Man and Galaga—and we expanded it. Our creative team was, like, “Hey, we’ve done this open-office vibe for two decades now. We want rooms. We want our own offices.” And so we built independent, individual, 10 offices, 11 offices, so that each of the graphic designers has their own space, but it’s no ceiling. And so, it’s both still open and unique and individual. And so that seems to be making them want to be here.

Retention is my word, because I want to make sure we’re retaining good people. We’ve got the greatest team we’ve ever had. How do I keep them happy? And I guess that’s why I’m asking the question: What’s far enough? What’s too far? Where’s middle?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, I don’t know how many people you have. But just a couple things came to my mind. The way I see this, because I think we lean in pretty hard toward people first, as well, and retention is a big driver behind that. But we’ve also got other things to our culture that we want to be intentional about. So it’s not just to retain. It’s to retain and to support collaboration. It’s to retain and to support high performance. It’s to retain and to support our inclusive environment. It’s to retain and to support high levels of customer satisfaction. And so we tried to get very specific about the why of the culture, not just good culture. So people say, “I just wanna have a good culture.” Well, yeah, but like, let’s define specifically what good is.

And then to me, you take a long-term view, like you would a portfolio of investments. So you named a bunch of things, and I would call that the portfolio: pay, work conditions, office environment, flexibility, all that stuff, right? Paternity leave, maternity leave. All that stuff is the portfolio of stuff. And the question is—and I think this changes over time—which instruments in that portfolio are providing return? Because some of them don’t matter. I’ll give you an example: We’ve got a division in our business that they do not value long-term incentive at all.

Jaci Russo:

Oh.

Mel Gravely:

They just don’t care about long-term incentive.

William Vanderbloemen:

Totally agree with that.

Mel Gravely:

So the portfolio, including long-term incentive for them, they’re like, “Okay, I’ll take it. But could you give me two more bucks an hour, because that’s really what I care about?” And so, figuring out and making sure you stay contemporary around your portfolio balancing. If you see it as a portfolio, then you can kind of manage it that way. And checking in regularly: employee-engagement surveys.

And if your team is small enough, I’d just talk to them and find out, in my one-on-ones, what matters. And once you’re like, “Yeah, I’ll take it, but I don’t really care,”—because it’s all costing money, right? And so, I take away the things they don’t care about, and double down on the things they do care about. And in three years, that’ll probably change. That’s my thought.

Loren Feldman:

Mel, are you referring to, like, a retirement plan? Is that the kind of thing that’s too distant for them to be concerned about?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, for some of our employees, even the yearly profit-sharing is too far out.

Loren Feldman:

Wow.

Mel Gravely:

But for sure, if I enhanced our 401(k) match, they’d be like, “Okay, that’s cool,” but they don’t care. They just don’t care. And I’m not judging them. What we often do is to create the portfolio based on what we value. And I think we’ve got to ask our people, if it really is about them: What do you value? And then how do I create that portfolio for them?

Loren Feldman:

Although it creates an interesting tension there, because you may think they’re valuing things incorrectly and that they really need the retirement plan. How do you think about that?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, so in this scenario, what we’ve done is made sure we retained a retirement plan for them. But we treat it differently than we treat another division in our company, because they value the long-term piece of it. So we didn’t take it completely away, Loren, but we’ve bifurcated the two organizations enough so that we can tailor it toward what those organizations like and appreciate.

It is unfair, and it is against one of our values of valuing the individual, to tell them what they should value. I’m not allowed to tell people what they value. I’ve got to listen to what they say and value what they value, because they may be in a life circumstance where, you know, they’re right.

Loren Feldman:

Jaci, I’m curious. It’s kind of obvious what the risk is if you don’t do enough, you could have an empty office. What do you perceive as the risk if you’re doing too much?

Jaci Russo:

That’s a great question. I don’t think that I would ever be accused of not doing enough. I’m a lot every day. And so, the doing too much for me, it’s about: I don’t want to create a sense of entitlement—which, I don’t think this team are those people. I am always cautious, because we’re getting ready to gear up our interview cycles again. And so I want to make sure I’m not attracting people who are coming just for the benefits and are going to be a bad culture fit with the rest of the team. I don’t want to bring in any toxic people. And I want to make sure that we are all in a good place.

And I’m really listening to what Mel just said about making sure that we have the… I love the way you said it. I can’t repeat it. So I’m trying to paraphrase it. Just about making sure we’ve got all those right fits together. Because it’s like, how do I make sure I am giving them the short-term that they want and the long-term that they need? Because I’m a firm believer in the long-term.

We do 401(k) match and vest from day one, because that is so important to me. And I think maybe I care more about them saving for their retirement than they do, and I’m okay with that. But then I think about: Oh, wait, you don’t want profit-sharing and commission and bonuses? You just want a bigger salary? Well then, are you really invested in the growth of the company? And then, should I care about that? Because you don’t own it. So should you care about it as much as I do? No. So these are the things that swirl in my head.

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, I think those are all the right things, though. And that’s why I like to look at this thing as a portfolio, because it can be balanced. I can make decisions to move money from here or there. But Loren, you asked an interesting question: Is there a risk of doing too much? Or what is the risk? And I think there’s absolutely a risk of doing too much, and it has nothing, in my mind, to do with entitlement—although that could be one of the outcomes.

To me, the risk is it could make you uncompetitive. So something has to give. You’re only able to bill the customer what you can bill the customer. And imagining that your fees and your value proposition are lined up, then there’s only so much margin to be spent on people. And if I get it out of whack, I can either become uncompetitive with my customer or become uncompetitive with my ability to make money and my ability to reinvest in the organization—not just as people, but in innovation and other technologies that I might need or in R&D. And over time, I can erode my ability to be competitive. So I am worried about doing too much—not because I don’t want to care too much. It’s because there’s only a dollar to go around.

Jaci Russo:

Right. That’s smart.

Loren Feldman:

William, I think I heard you agreeing with Mel about the issue of people not thinking long-term. How do you deal with the question of whether you give people what you think they should have or what they think they should have?

William Vanderbloemen:

Well, I’m learning as I go, Loren. Two things that I have found personally that help—and I’ve heard from colleagues who also own businesses that they have the same learning—one is, anytime I’m about to add a benefit or a piece of culture to the office—even down to: Do I sign a 10-year lease on the nice office space or not—I’m asking myself: Is this a one-way street? And what I mean by that is, there are some benefits that I’ve seen in business that are very, very hard to revoke.

Here in Houston, we have a massive turnover within the energy industry. Everybody kind of bounces around once bonuses pay out for the prior year sometime in March. The energy recruiters go crazy, because everybody’s ready to move to the next thing. So there’s always the retention question, and one of the things that the oil and gas industry instituted many years ago—it may be in other places as well—it’s called the 9/80 workweek. Is that a term you guys know?

Jaci Russo:

No, tell me.

William Vanderbloemen:

Okay, so the idea was: Look, it’s kind of the predecessor to remote work or hybrid or take all the vacation you want. There are a lot of iterations of this get-your-job-done-and-we-don’t-care-if-you’re-here kind of mantra. So 9/80 meant: We’re going to work 80 hours in two weeks, and we’re gonna get it done in nine days. And every other Friday, you have off. And half of the company is the A team, and half the company’s the B team—not by value, just by grouping. And half of you are off this Friday. The other half are off the next Friday. And, you know, it sounded great.

The byproduct was the team that was there on Friday wasn’t getting anything done. A lot of them were using their PTO for the Fridays they didn’t have off. And there was no policy in place for: You can’t keep taking Friday as your day off. And then, years later, when this became kind of untenable for a few companies, they tried to take it back. And they put pay raises in. And they put better food in the cafeteria. And it didn’t matter. The 9/80 was kind of a one-way street. And the company that was a really good company that tried to revoke it couldn’t get anybody to come work for them.

So the question I’m asking, in my mind, is: Is the benefit I’m offering going to be harder to undo than then the benefit that it reaps for doing it? And, like I say, I’m still figuring that out. We’ve tried to gamify everything. Our COO did a wonderful job. A lot of our work is very collaborative and very difficult to do remotely. So we have consultants on the road, but the in-house team, they really benefit by being together. But you’ve got to do some things remotely. So Jennifer, our COO, said, “What if we did this? We’ve got five core teams in the office. We’ll set stretch goals for them every month—real stretch goals, not fake ones. And if the team hits the goal for the month, the next month, they can do Wednesday’s remote until they don’t hit the next month’s goal.”

So she found a way to keep it from being a permanent fixture in our culture, and more of an earned reward. And that’s worked really well for us. “Is ending it gonna be more painful than the good that I get from instituting it?” would be kind of the baseline question that I ask when I’m trying to figure out: How do we do this? And is this too much?

Loren Feldman:

Jaci, did you worry about that when you went to the four-day workweek?

Jaci Russo:

Oh, well, I did a lot. Because I knew that once we started it, we weren’t going to get it back. And Michael, my business partner and husband, was adamantly opposed to it. Like, “Absolutely not. We’re not doing this. This is a mistake.” I’m like, “Okay, let’s just try it for three months and see how it goes.” And so we had real clear communications with everybody,

Loren Feldman:

But you knew you couldn’t do that, I think you just said.

Jaci Russo:

Well, yeah, but that’s how I got him to agree to it. Are you not married? Do you not understand the way people work together? [Laughter] Come on, Loren. Yes, that’s how I got my way. But so we communicated with everybody that it was a three-month trial. We were gonna test it out. And I’ve mentioned this on the show before: I went to the two people who have the hardest time with deadlines and constantly say, “I’ve got too much, I’ve got too much,” and said, “Hey, I’m about to take a whole workday away from you.” Before I can finish the sentence, “We can do it.” And I said, “But you’re—” “Nope, we can do it.” And to their credit, neither of them have missed the deadline or needed to punt a project. They have managed to get done in four days what they could not do in five days before.

Loren Feldman:

Mel, I’m curious how, when you’re thinking about these kinds of issues and other issues managing a business, you factor in the role of your economic outlook. I don’t think any of us are economists, and no need to pretend that we are. But the expectations for the economy have been bouncing around so weirdly the last couple of years. We’ve been assured a recession is coming. It’s never come. And in talking about the risks of going too far here, obviously, the risks get greater if the economy struggles. How do you think about that at a time like this, planning for the year ahead?

Mel Gravely:

Great segue. We try not to plan too short-sightedly. So what I mean by that is, we wouldn’t not bring a new employee opportunity to our team because we were worried about the next year. We might make less money that next year, but our horizon is so much longer that we’re okay with a tough year. And I don’t mean losing money. But I mean maybe not hitting our growth objectives, maybe not maximizing our profitability. We’ll trade off in other areas.

But we wouldn’t pull back on an employee benefit. We wouldn’t not make a decision to employ one because of the economy. I’ve never been in a conversation in our company where someone said, “We’d better not do that now because of a looming something else.” And I think that’s the advantage of having a longer-term perspective. And since we’re privately held—I control most of the shares—if I’m willing to say, “Well, let’s just make less money next year,” then that usually makes the conversation much more strategic.

Loren Feldman:

You probably didn’t say that earlier in your term as owner of the business, I’m guessing.

Mel Gravely:

I’m not sure. You know, we’ve never lost money either. So that does make it easier.

Loren Feldman:

Oh, that helps.

Mel Gravely:

But I was older when I started this, Loren, or when I bought it. And so I do think early on, we made really long-term decisions and believed that they were going to, over time, work out for us. And there were many years where we just decided, “Okay, we’re just going to make less money.” But what we want to do is so important for who we want to be that we can’t not do it.

Loren Feldman:

How about you, William? How do you think about the economy when assessing your hopes for the coming year?

William Vanderbloemen:

Most of our work is executive search for faith-based organizations. So, churches, faith-based schools, faith-based nonprofits, even the faith-based for-profits of the world, like Chick-fil-A. So in the faith-based world, the old joke is: The only thing more recession-proof than religion is alcohol. [Laughter]

I don’t know if that’s true or not, but—maybe it’s because we started in the fall of 2008, which was a stupid time to start a business— but we haven’t had a, “Oh crap, the external factors of the economy have vastly shifted our forecast for the year.” Maybe it’ll happen. Maybe it’ll happen this year or next. But to me—

Loren Feldman:

Wait, it happened during COVID, right?

William Vanderbloemen:

Well, that would be the one exception. I didn’t go to business school, but I learned a lesson during COVID. If all of your clients close indefinitely, it will change your calendar and your P&L. [Laughter] So I kind of laughingly say: We had to make a massive reduction, as Loren knows, during 2020. We still did not lose money that year—and that’s a whole other podcast episode. But since then, ‘21 was our best year ever. ‘22 is better than that. ‘23 was massively better than any year we’ve ever had.

So we’ve just been very fortunate. And I might not be the right guy to ask, because we have introduced a new idea into our potential client base—I don’t wanna say new industry—but a new option. And it is very quickly gaining traction as the normal way to do things. So maybe if I’d already saturated the market, the economy would make me go, “Oh, gosh, we’re gonna lose 10 percent of our customers.” But we have so many new clients every year that I don’t know that I have the most sober view of what the economic outlook does to our planning. Does that make sense?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah. By the way, I want to add that caveat: Of course, we paused every thought during COVID. So, thanks, William, for reminding me about that. And you know, it does matter when you start. I mean, I bought this company in 2009. So it was as bad as it could get in 2009. So I’ve only seen improvement—not steady, but general improvement, in construction volume and our ability to attract new customers. So I’m with William. I’ve not seen a really, really bad storm. So, Loren, my mind might change, if I do.

Loren Feldman:

Are any of you thinking of making serious investments in your business this year? And is that related to the economy, or just related to your position in your various markets? Anybody?

Jaci Russo:

We are. We’ve looked at acquiring another agency, and so we’re continuing to evaluate options like that. We think it’s a good time to grow. We had the great fortune of growing during COVID, and the next year, and the next year. And so, we’ve just finished our fifth straight year of growth. And time’s ticking. I’m only going to be around so much longer. So I want to make sure I’m maximizing every opportunity I’ve got.

Mel Gravely:

I’m with Jaci, though. I think this is a time to double-down. And I think there are gonna be more opportunities. I think people are gonna be parachuting out of their businesses. They got kind of happy over the last few years. I think reality will start to set in over the next few, and the grind will start again. And I think there’ll be some opportunities for acquisitions.

We are almost constantly working on a deal or two right now. And they don’t all work out. They don’t all close. But we think it’s a good time. We particularly want to come out of the next three years with just a whole lot more capability. Forget size, we want more capability. And with that will probably come size, too. But its capabilities to do a broader set of things is what we’re after.

Loren Feldman:

So not size, just for the sake of size, but buying skills, people with talents, that you don’t currently have?

Mel Gravely:

Yep, and some vertical integration, so we can do a little more self-performance and control our own destiny in some areas. But not growth. Like, I don’t know if we’d buy a company that had a profile just like ours. I’m not saying we wouldn’t, but it just wouldn’t be as attractive as it would be to buy a subcontractor or something that enhances our capabilities.

...

Read Full Podcast Transcript Here

.png)