Introduction:

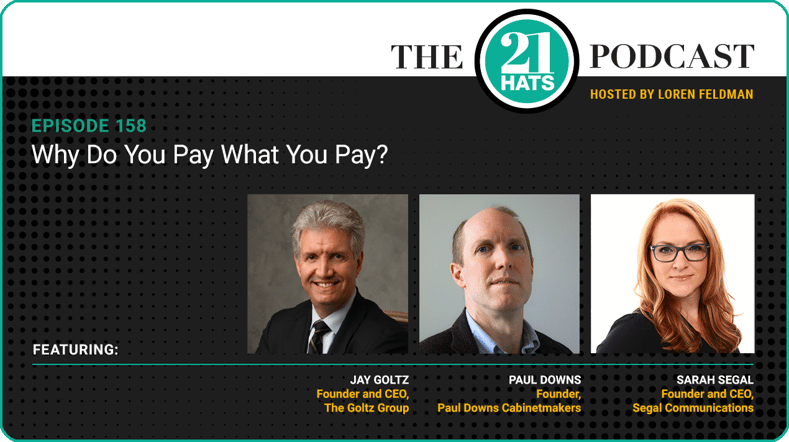

This week, Paul Downs, Jay Goltz, and Sarah Segal talk about where the dust has settled after years of turmoil in the labor market. As you know all too well, we’ve been through COVID, supply-chain issues, inflation, labor shortages, the Great Resignation, minimum-wage hikes, new pay-transparency regulations, and countless rumors of recessions that have yet to come—all of which has had an impact on wages. And that’s why I decided to ask Paul, Jay, and Sarah where their thinking has landed. The consensus here is that leverage is shifting back to employers, but Paul, for one, remains committed to paying his people more than they can find elsewhere. “It’s worth it to me to have the team I want,” he says. “And sure, it affects profitability, but turnover affects profitability, too. And I’d rather not have that.” Plus: We also talk about whether Lululemon was right to fire two retail employees who tried to stop a robbery, and we answer the following listener question: If something’s not working, how do you know when it’s time to walk away?

— Loren Feldman

This content was produced by 21 Hats.

See Full Show Notes By 21 Hats

Podcast Transcript

Loren Feldman:

Welcome, Paul, Jay, and Sarah. It’s great to have you here. I wanted to start today by talking about employee compensation. As we all know, we’ve been through a lot of turmoil the last few years: COVID, inflation, the labor shortage, the Great Resignation, all things that have had an impact on hiring and wages. I’m sure I’ve left something out.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, there are five things that have changed: COVID, inflation, labor shortage, minimum-wage changes, and the fact that people are now posting how much money you make in ads that we didn’t use to do.

Loren Feldman:

Pay transparency.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah. Whether it was forced or not, it’s become clear that it does help your response rate. So yes, that’s a lot is right.

Loren Feldman:

So I guess my question is: Why are you paying what you’re paying? And are you happy with where you landed? Maybe Paul, start with you?

Paul Downs:

Why am I paying what I pay? I tend to pay high, because it takes such a long time to train my staff that I don’t want them going anywhere.

Loren Feldman:

So that’s been true for a while, I assume—well before COVID?

Paul Downs:

Yes, that’s always been my strategy, which is: I don’t want people to have a better situation that they can easily waltz into. And including pay.

Loren Feldman:

When you say higher, do you have a set percentage in mind over what you think is the market rate?

Paul Downs:

Not really. It’s mostly: Are they making $25 an hour-plus in total compensation? Which I think of as kind of a baseline for being able to survive in my area. And then some employees make considerably more than that. And those are the ones who have professional degrees or whatever, and they have options. They could go get another job anytime.

So I focus on staff retention, and part of that is pay. And part of that is just providing a good working environment. That said, yeah, I had to give a bunch of people raises the last few years. People just come into my office and say, “I want a raise, bup, bup, bup.”

Jay Goltz:

I think part of the key, in your case, is part of your business model is you’re selling a premium product, which is why you can afford to pay more because you’re giving a premium product. It all makes sense. You’re not selling a commodity.

Paul Downs:

Yeah, exactly. It’s worth it to me to have the team I want. And sure, it affects profitability, but turnover affects profitability, too. And I’d rather not have that.

Loren Feldman:

So Paul, when somebody comes into your office and says, “I want a raise, bup, bup, bup,” do you give them the raise? Or do you make them go get an offer?

Paul Downs:

No, no, no, I don’t want anybody looking around. Usually I give them a raise. Because, generally, there’s a reasonable case to be made for it. Often I hire people, and a year later, the ones who are really good, they’re like, “Hey, I’m good.” I’m like, “Yeah, you are, here’s some money.”

So there’s no huge calculation on my part as to exactly what it’ll be. But one thing I do keep careful track of is what their total compensation works out to in pay per hour. Like if you roll in all the costs of the health insurance and everything that we do, I’ve got a spreadsheet that divides all those numbers into the number of hours they work. And I can say to them, “Okay, you’re only getting paid what you think is 20 bucks an hour, but I’m covering health insurance for your wife and three kids. And that’s another 11 bucks an hour. So, surprise! You’re actually making $31. It’s just that some of it is in a form that you hate.”

Jay Goltz:

Paul, I assume from knowing you, I think you try to stay ahead of this and you’re trying to pay appropriately. So I’m sure this happens, but it doesn’t happen that often, does it? Because you already are staying up with it. I mean, this isn’t a monthly event.

Paul Downs:

Yeah, I would say, actually, that the proportion of times I have simply given people money, as opposed to them asking for it, is maybe three to one. LIke, for instance, you hire someone and you have to think about, “Okay, well, I hired this guy. I need to pay them X to get him in the door. Do I need to recalculate some of the other people in that case, just to be fair?” I mean, that’s a pretty common scenario. And then other times, there might be someone who’s shy and just is afraid to ask me, and they’re doing well. And I’ll be like, “Hey, it’s been a year. What do you want?”

Loren Feldman:

Seriously? “What do you want?”

Paul Downs:

Yeah. Okay, let me just give a warning to everybody listening to this: The things I do, you probably should not do. Because I really am biasing the whole thing towards staff retention and investing in people over a series of years, because that’s how long it takes to train people up. And so, no, I’m not doing a lot of things. I’m sure Jay has a completely different playbook.

Jay Goltz:

I wouldn’t say completely different. But you’d be correct—different, in that you are truly dealing with skilled labor. And I’m dealing with semi-skilled in some cases, and unskilled in other cases. So I fully understand what you’re saying—in your case, you’ve got skilled labor that takes you years. You really can’t afford turnover. In my case, I can afford a little turnover. But it’s also not 180 degrees from what you’re doing. I also have very low turnover. My turnover is probably 10 percent.

Paul Downs:

Yeah, mine’s less than that. I only had one employee leave after COVID—voluntarily. And that was because he just got tired of the commute, and so he found a job that was closer to home. It was too bad, because he was a fantastic engineer, and we miss him. We were able to replace him, but money wasn’t really the issue, at that point. I would have given him more money, but I couldn’t find a way to not have him spend 45 minutes in a car each way.

Jay Goltz:

I’ve gotta tell you, traffic has become a major factor in employment these days.

Sarah Segal:

Jay, don’t you have somebody who has a commute of, like, an hour and a half each way?

Jay Goltz:

Yeah. And he’s been with me for 25 years, and he’s a critical person. I’m tight with him. And he’s totally with me on the whole mission. But yeah, he drives a long time.

Paul Downs:

That’s crazy.

Jay Goltz:

But you know, he’s a six figure guy.

Paul Downs:

Six figures, but that’s still an incredible—that’s 1,500 hours a year.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah. Let me add a piece of this that I don’t think either of you have to deal with, which is minimum wage. In 2014, the minimum wage in the city of Chicago—because there was no special minimum wage for Chicago versus Illinois—was $8.25. And as of next week, the minimum wage in Chicago is now $15.80.

Sarah Segal:

Wow.

Jay Goltz:

Which means it’s gone up 91 percent in nine years, which is about 10 percent a year. That does have an effect on things. And it’s caused what I call “labor compression,” which means the spread between the top person and the bottom is not as much as it used to be. And part of it is simply because, when you think about it, if one person can frame, whatever, 10 pictures a day, and the other person can do five, one could say, “Oh, well, they should make twice as much.” That doesn’t really work. Because at the end of the day, everybody has rent to pay and has food to buy, which is why I fully support minimum wage. It’s compressed, though, meaning maybe at the bottom, they’re making $3 an hour more, but that doesn’t mean it went all the way to the top. That has to be factored in.

Loren Feldman:

Tell us about the impact that that increase had on you specifically. Were you paying many workers the minimum, at that point?

Jay Goltz:

I’ve been close. Over the years, close. And I’ve definitely had to build that into my cost of doing business. I would say this: I just lately had a case of every one of those five things I mentioned, they had a profound impact. You put them all together, and that’s a lot of moving things. And I have had to sit down and think, “All right, what is our starting wage going to be? What is the marketplace?” We put ads out there. We’re not getting a lot of responses. There are less employees.

So we just had a situation where somebody came to us and complained that we’ve been trying to find someone for a particular position, and now we’re putting it in the ad. We raised how much money we were offering. And she goes, “That’s almost what I’m making, and I’ve been here for two years.” And you know what? She had every right to be upset. And we talked about it. And the fact is, we gave her a raise, and we’re going to give other people in that department raises.

So part of my feeling on this is, I feel good that she felt comfortable coming to say something and that she didn’t just quit. And we apologized. We said, “You know what, we didn’t react quick enough to the changing dynamics of the marketplace.” We fixed it. She’s happy, we’re happy.

But yeah, we did get caught a little bit on our heels with that, because we didn’t change it quick enough. Because it’s definitely affected the marketplace, especially the fact we’re putting it in the ad now—how much we’re paying—which we never used to do.

Loren Feldman:

Are you required to do that, Jay?

Jay Goltz:

I don’t believe it’s become a law in Illinois yet. But here’s the big but: But, I keep reading, they keep doing studies. You do get more respondents when you put it in the ads. So we’re going with the flow, and we put it in there. And I think it’s true. You also get less tire kickers, because they can see what you’re paying, and they’re not going to bother if it’s not what they’re looking for.

Sarah Segal:

Where are you, in terms of your salary ranges for your positions? Did you increase them over the last year?

Jay Goltz:

Absolutely. Because of inflation, we probably did 5-6 percent, which we haven’t done in many, many—I don’t know that we’ve ever done that. Inflation has been next to nothing for years. We were good with 2 or 3 percent. So we definitely gave a bigger raise. I don’t think it’s going to continue this year, but time will tell.

Paul Downs:

When you asked about the range, do you mean like I pay from $40,000 a year to $110,000 a year, or something like that?

Sarah Segal:

Per position. So if you have somebody who’s a sander—I don’t know what you have—but you know, last year, your starting salary for that position was $35,000.

Paul Downs:

No, most of those people, they’re making in the mid to upper $20s per hour with some variation on what their benefit package is, because we offer to cover employees. Whatever dependents they want to bring, we pay for part of that.

Sarah Segal:

Do you think that we’re in an employers’ market or are an employee’s market right now?

Jay Goltz:

I think it’s evened out.

Paul Downs:

I think it’s not quite as employee as it was, but it’s not 2009. That’s for sure.

Jay Goltz:

Right. I think it’s in between.

Sarah Segal:

Well, here in California, I definitely think it’s migrating entirely to an employer market. Because I mean, I look at my LinkedIn feed and you know, “open to opportunities” and “looking for jobs” is like every other post, at this point. Just because we’ve seen so much of the tech stuff implode here on the West Coast. I increased my salary ranges last year, and it wasn’t for inflation, but it was for getting people to apply.

Jay Goltz:

I will tell you that this quote-unquote problem is an opportunity, because some of your competitors—some of my competitors—are knee-jerking and not giving any raises. And it’s pissing people off. It’s an opportunity to get some good employees who their bosses have gotten short-sighted and forgot the quote-unquote greatest asset is their people. And I do think it’s freeing up some good employees who might not have been looking before, which is what I think you’re saying.

Sarah Segal:

Agency size is a little weird, though. When you’re a boutique agency like me, I can’t compete with the big guys, in terms of their salaries. I just can’t. And I’m surrounded by tech companies that are hiring people straight out of college with six figures. I cannot compete with that. So really, what I have to offer is the full package. We will really have respect for people’s work-life balance. We really have a great PTO plan.

Jay Goltz:

I think you’re right, but the fact is, that is competing. The fact is, you might not financially be able to compete, but you are competing. And I’m in the same situation. You were here a couple weeks ago. I had two different employees tell me they had job offers from major retailers in the United States that came to work here because they want to work in what I call a collaborative environment. They want to matter, and they don’t want to deal with corporate politics and stuff.

We can compete out there. There are people out there now who will give up money for working in a nice place. And to your point, the hours thing. Some of these people… I brought back somebody who was making 30 percent more at one of the big companies. They were just killing them: 60-, 70-hour weeks every week.

Sarah Segal:

Yeah, I’m small enough where we have summer Fridays, and nobody puts “out of offices” on summer Fridays. If there’s something urgent, we respond to it. But if a team member is going to be out, and they don’t have anybody to cover because their partner-in-crime is at a conference or something like that, I’m like, “I’m here.”

I’m always a person who people can call, because I never put “out of office.” Because I want people to be able to disconnect and for people to go off the grid and really kind of have that opportunity to get refreshed and motivated and inspired by life. But corporate? You don’t really do that as much.

Jay Goltz:

No, and there are plenty of people out there who value that more than money.

Loren Feldman:

Sarah, when you raised your wages last year, how did you figure out the number where you settled?

Sarah Segal:

Well, we’re lucky, in that we are part of a number of different professional PR organizations, one of which is really great about doing surveys where people provide transparency in what they’re offering people. And we also look at what other people are offering. More and more companies are posting the range, at least. And so we just bumped it up by a small percentage, but it just makes it a little more competitive.

But you know, part of me is like: Inflation is going down. The job market’s becoming more tough. I’m thinking maybe later this year, I can reconsider those increases, depending on what things look like. Because, honestly, I think I’m paying somebody out of college way too much. I mean, I made peanuts when I got out of college, but it was a great job, and it was a cool opportunity, and I loved it. And it wasn’t about the money.

Loren Feldman:

Paul, I want to go back to that conversation you have where you turn to your employees and say, “How much of a raise would you like?” I’m curious, do you get realistic responses? Are you often able to meet their request? How does that go?

Paul Downs:

You know, you do that with people who are afraid to ask for raises. So they’re generally delighted that I’ve recognized them, and I rarely get an answer back. And so I’ll say, “How about X?” And they’re pleased as can be.

Sarah Segal:

I don’t think people are greedy. I think when you ask a question like that, someone’s not going to look at you and be like, “I want $10 million a year.” They’re gonna look at what they do, and give an appropriate answer. I just think with human nature, most people won’t do that.

Paul Downs:

The other thing is, it’s just a basic negotiating tactic. It’s better to get the other person to name the first number.

Loren Feldman:

Well, I was gonna say, what if they ask for less than you were prepared to pay, what do you do?

Paul Downs:

Depends on what they ask for. But sometimes I give them more. That particular conversation often happens at the point where I’m deciding to hire somebody. And I’m interviewing them and I say, “What do you want? What are you looking for?” And if I want to hire them, they tell me, “X and such dollars an hour.” I’ll say, “Listen, I’ll do X plus one. I want you to accept this job right now, though. I’m gonna take you off the market because I want you to work for me.”

Jay Goltz:

He’s watching too much “Shark Tank.” That’s the problem.

Loren Feldman:

Paul, you told us that a while ago when the labor shortage was acute. You’re still doing it?

Paul Downs:

Well, yeah. It is a tactic that’s predicated on the employees-in-charge labor market. And when the time comes that we flip back the other way, I may rethink it. Or I may not, because I think that it’s a statement of faith and a statement of the kind of relationship I want to have with my employees at a moment when, for the person who’s thinking of joining us, it’s a big risk. They don’t know what they’re walking into.

So if the boss is right there saying, “I think you’re gonna be great. And I want to give you more, and I have faith in you.” And the next thing I say to them is, “Okay, I’m gonna pay you this. And if it turns out I’m mistaken, I’ll get rid of you. And so it’s on you now.”

Loren Feldman:

There goes that goodwill.

Paul Downs:

Well, no. It’s being honest. It’s just like, I’m not going to let someone take advantage of me. But I will—

Loren Feldman:

But do you need to say that to them? Do they need to be told?

Jay Goltz:

Do you actually use that language? Or do you say, “Listen, if it turns out, you’re not worth it, it’s not gonna be working for either of us, and you’re probably going to leave”?

Paul Downs:

No, I say, “We’re gonna give you all the support.” We have written down new employee guidelines that tell them exactly what they need to do. And I say, “We’re making an investment in you. But if it doesn’t work out, I will fire you. It won’t last long. So first thing: show up, act interested.”

And I just give them what’s going to happen. I don’t like to sugarcoat stuff, or be vague about something that I have in my mind as a possible course of action. And I’ve had, as far as I know, very little negative reaction to that. Because again, it’s establishing a relationship, an honest relationship, right from the get go.

Read Full Podcast Transcript Here

.png)