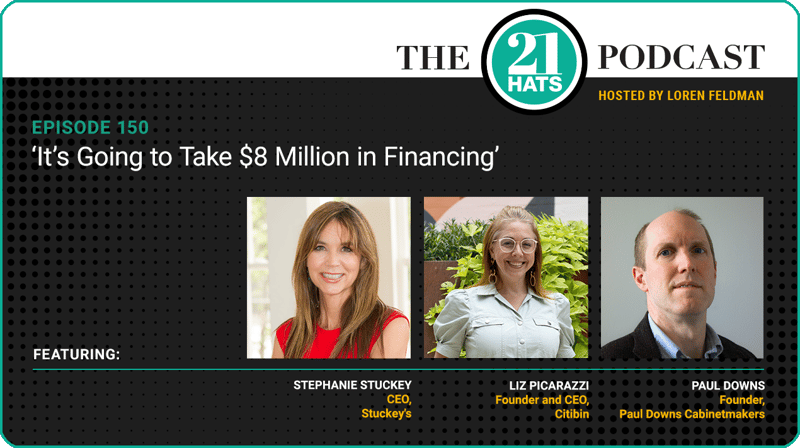

This week, in episode 150, Stephanie Stuckey tells Paul Downs and Liz Picarazzi how she and her partners have taken their business from $2 million in annual revenue to more than $13 million in three years. What’s frustrating, she says, is that she could be selling a lot more pecan snacks and candies. But with production at capacity, she’s not doing much sales outreach until they can fully revamp their manufacturing operation, which will require a significant investment. “I spend my days doing financial paperwork,” Stephanie says. Plus: Liz explains why her business picks up when the weather warms up, and after a slow start, Paul gets a boost from a big manufacturer.

This content was produced by 21 Hats.

See Full Show Notes By 21 Hats

Podcast Transcript

Loren Feldman:

Welcome to the 150th episode of the 21 Hats Podcast. We’re here today with Paul, Liz, and Stephanie. It’s great to have you all here. And it’s especially great to catch up with you, Stephanie. I know you’ve been busy. How are you? How’s it going?

Stephanie Stuckey:

I’m doing great, thank you. I have been busy. It’s nice to be back.

Loren Feldman:

Well, welcome. Tell us, I think it’s been more than a year since we’ve talked to you. How did last year go for you?

Stephanie Stuckey:

So just for background, for people who might be newer to the show and not remember the story, I am the third generation of a family business, Stuckey’s, founded by my grandfather. He sold the company in 1964. It was out of our family’s hands for decades. I had the unexpected opportunity to buy it three years ago. It was six figures in debt.

People familiar with the brand probably know us as a roadside convenience retail chain. We only have 60 locations today, and we don’t own or operate any of them. They pay us a licensing fee. So we had to rebuild the brand in a way that would make us more profitable because we don’t generate a lot of funds from those licenses. So we purchased a manufacturing facility that shells pecans and then makes pecan snack candies and pecan snacks.

So that happened two years ago. And in the past year, what we’ve done is we decided to get out of the shelling business. That was a big move for us. We’re in the process of moving and selling all the shelling equipment. And we’re doubling our capacity to make the finished product. So we’re going to make more pecan snacks and more pecan candies because the demand is growing.

So we’re getting more machinery. We’re hiring a new workforce. We consolidated all of our operations into one place. So we moved our distribution center, which had been in another town. We just moved that. We just upgraded with scanning technology and real-time inventory. We just finished integrating all three companies that we’ve purchased into one financial system. So just a lot of internal structural work to strengthen and grow our capacity. And really, I think by Q4 is our goal to start growing with sales, because we’ll now have the capacity to actually fulfill. It’s been a lot.

Loren Feldman:

That is a lot. While you were doing all of that, did your revenue for last year meet expectations?

Stephanie Stuckey:

No, I’ll be honest. I think quite often there’s this thought that you’re always on this trajectory of going upwards, and the sales were on a trajectory of going upwards, but the net was not, for several reasons. One is we’re putting in these processes, so that all takes time. So we weren’t as diligent as we should have been on our accounts receivable, for example. If we had been collecting like we should, and we had a strong process in place, we would have ended the year much stronger.

Now we’ve collected those, but it took us a while to put that process in place. We also gave three rounds of pay raises to our workforce. And that was our biggest expense last year, and it was the most important expense, because we really had to shore up our workforce. So turnover has gone down dramatically. Workforce satisfaction has gone up. We’re doing a lot of work with culture and employee engagement, and all that’s paying off, but it takes a while. It takes an investment of money and time and energy to put the structure in place so that you can start growing.

Loren Feldman:

What were the companies that you bought?

Stephanie Stuckey:

So there’s Stuckey’s, of course. And then my business partner had a snack brand called Front Porch Pecan, so we had to merge his records with our records. And then the two of us jointly bought, like six months later, the manufacturing facility in Wrens, Georgia, which includes the shelling operations and the candy operations and a fundraising business. And actually, those three entities all kept separate books, and were all organized as separate legal entities. So we’ve had to consolidate all their books.

I think too often we read about these mergers in the news, and we think it’s: Once you sign on the dotted line and you transfer the paperwork and the finances, that it’s done. But no, integrating the financials, integrating the culture, integrating the workforce, making sure you’re not duplicating roles. Or maybe you want some redundancy, and making sure people understand what each other is doing. We’ve had to completely redo our org chart. So that’s taking time. And now that we’re really close to having everything in place, I’m excited. I feel like I can start focusing more on sales, and less on logistics and supply and HR and finances.

Paul Downs:

I have a question.

Stephanie Stuckey:

Yes.

Paul Downs:

The last time you were here was pre-COVID. Right?

Stephanie Stuckey:

No, I was here during COVID.

Paul Downs:

I’m just wondering how that general disruption and travel and what have you affected the brand.

Stephanie Stuckey:

Not really, because people continue to buy snacks and candies. And we’ve been expanding the channels where you can buy our products. So we’re not just distributing to those 60-plus Stuckey’s licensed locations. We’re now in some 5,000 stores nationwide through distributor networks. Some of the larger chains would be Food Lion, Ingles, Wawa in Florida. We’re in some Big Lots, At Home. We’re about to be piloted in Pilot, and TA as well, Travel Centers of America. And we have a lot of mom-and-pop locations all over the country that sell our products: Ace Hardware and local grocery stores, and gift shops, hotels. You name it.

Loren Feldman:

You had told us about that a little bit, Stephanie. And I think one of the challenges you faced was figuring out how to price your goods, depending on where they were being sold. How has that worked out for you?

Stephanie Stuckey:

You know, I’ve learned, and it’s a process that there are different pricing models for different channels. So if you’re going through a distributor, obviously, you’re going to have to alter for distributor pricing. And if you have a broker, then the broker’s going to take their whatever, 3 to 5 percent. And the distributor is going to take their 30 percent. And then if you’re in the grocery channel, then the grocer is usually going to be 33 to 50 percent.

So there’s that whole world, and I would put Costco and Walmart and some of those in that category. And then you have to pay the slotting fees. You have to pay the upfront setup fee for the warehouse. The fees are phenomenal. And then you’ve got the specialty retail, which has a lot more flexibility on the price structure. We distribute direct to them from our distribution center. So the specialty mart in Fort Smith, Arkansas, for example, might have a higher retail price, but you’re paying for being in a nice store environment.

Paul Downs:

You went from 60 outlets to 6,000? That’s really impressive.

Stephanie Stuckey:

About five thousand. But it’s through the distributor networks, right? So they’re different types of—

Paul Downs:

Yeah, but, you’re there, right?

Stephanie Stuckey:

Yeah, and we’re online. Yeah, and fundraising, too, is a huge business for us.

Paul Downs:

Very impressive. Well done.

Stephanie Stuckey:

I was just looking at our fundraising numbers this week. Last year, we did over $3 million in sales for fundraising.

Paul Downs:

Can you tell us what your annual sales are now, as opposed to where you were?

Stephanie Stuckey:

Yes. In the past three years, we’ve gone from $2 million to over $13 million.

Paul Downs:

That’s fantastic. Congratulations!

Stephanie Stuckey:

Yeah! But we’re really held back. We could do so much more. And what’s so frustrating, is we are not proactively pitching accounts—other than our distributors will do pitches with some large retail chains to get us in a planogram, for example. But we’re not out there proactively marketing sales, because we don’t have the capacity to fulfill orders right now.

So you won’t see us on Amazon. You don’t see us on Faire.com, which is for specialty retail, because we don’t have the fulfillment capacity yet. So we’re trying to scale in a way that makes sense for us, so we don’t disappoint a lot of customers, because they place an order and five months later, we still don’t have the product ready.

Loren Feldman:

So I guess that’s what drove the decision to stop shelling and start making candy. Tell us about that decision. Are there risks in that? Do you lose some control by not doing your own shelling?

Stephanie Stuckey:

Honestly, after we started delving into it, we realized that the biggest hold back for us was that the facility we purchased had been shelling since 1935, and the community was used to us having a shelling plant there. But shelling operates from October through January. It’s seasonal. And we were having to keep this whole facility active. Like, we had all this space that we were paying for, we’re paying mortgage on, we’re paying—maybe not to keep it super chill—but we certainly had to keep it climate-controlled.

We had some staffers who we had to keep year-round because they were so valuable, and we really only used them five months out of the year. I’d go see them in the off months, and they’d just be sitting around talking and reading the paper all day. And I thought, “Why do we have you on salary?” We really employed them just a handful of months a year. Then we had to train a seasonal workforce every year. We had to ramp that up, and it was just exhausting. So now we have an exclusive contract with a pecan sheller from Georgia, Georgia Grown Pecans, and we’re actually going to save money not having to shell.

And then we can more than double our capacity to produce, but it’s going to take $8 million in financing to renovate the shelling facility to be food-grade certified. We have to get a new roof. We have to insulate. We have to air condition the whole section more, because we’re making chocolate, and we roast pecans, and it gets really hot in there. So there’s a ton of work that has to be done. And then we have to buy new equipment and hire up staff. So it’s about $8 million. I spend my days doing financial paperwork.

Loren Feldman:

How are you going to finance that?

Stephanie Stuckey:

We’re doing two different main ways. First is New Market Tax Credits. And that will bring in about $1.5 to $1.9 million, depending on how it all shakes out at the end. And that should close in two weeks.

Loren Feldman:

How does that work? I’m not familiar with it.

Stephanie Stuckey:

I was afraid you were gonna ask me that, and I have a very high-level understanding. And like any of these government-related financial programs, you almost always need to have a person whose whole role is to package it and organize it for you. And then they get a cut. So if our guy was on the phone, he could explain it better.

But basically, it’s a program to incentivize job creation in small rural communities or economically disadvantaged communities, often through manufacturing, and they really like agribusiness projects. And the federal government offers tax credits as an incentive. And there’s a mechanism by which you can sell your tax credits to third-party entities at a reduced rate. So you monetize your tax credit, and you get the tax credit proceeds right away to apply to whatever project you want. And then the entity buying the tax credit gets to use it over a period of years. So we actually get cash with no obligation on our end other than a bunch of reporting, which is why we have a guy who is going to take his cut to manage all of that process.

And then the rest of the financing is coming from a USDA Food Processing loan. And we’re working with Ameris bank in Augusta, Georgia, which is right near where our plant is, and they’ve been terrific. They do a lot of these USDA Food Processing loans. And they have the contacts, and they can pick up the phone and get the right person. And that should close in July.

Loren Feldman:

So you’ve been watching interest rates for some time, I’m guessing.

Stephanie Stuckey:

Yes, and that’s one of the reasons why we’re doing the USDA, because we purchased the plant with a SBA 7(a) loan, which is a variable rate, and those payments have been going up. We’re paying some of that down, and then we’re refi-ing with a USDA loan at better terms.

Loren Feldman:

Interesting. Stephanie, if I recall correctly, when last we spoke, you described the way you divvied up responsibilities with your partner as you being primarily focused on marketing. It sounds like you’ve gotten quite an education in manufacturing since then. Can you talk a little bit about what you’ve learned about manufacturing, and how this is going for you?

Stephanie Stuckey:

Yes, it’s really been all hands on deck. My business partner remains more focused on the operations end, but you have to understand that if you’re going to be a partner. And so I spend a lot of time just observing and watching. And I actually work shifts so I understand the process. And we have an overall plant manager, so he does a lot of that as well.

My role still tends to be more external and connecting with resources to help us get the workforce where we need to be. For example, Georgia Tech has a manufacturing program on a sliding-scale basis. And they’ll come in, and they’ll help you analyze how you can better do the layout of your plant. I’m better at big-picture thinking.

So after working a bunch of shifts, being very much in the day-to-day grunge work of running a candy plant and a snack-plant operation, I realized there were some inefficiencies in how we were laying out our equipment, and what the workflow was, and where we stored our ingredients. And so we all worked together on this, and we’re now reconfiguring the workspace. So that’s been a lot. Like, how do you have the workflow in a way that maximizes productivity? So that’s one of the things I’ve been doing.

And I’ll be perfectly honest, a lot of my time this past year has been building the connections that will help us as we start to grow. So I just joined the National Confectioners Association board of directors. That’s going to be a big commitment. I also do a ton of keynote speaking, events, so I’ve been traveling all over the country. And I get paid to do that, which has been really nice. And what I started doing was negotiating the pay: “Instead of paying me cash, I want you to buy $5,000 worth of Stuckey’s gift tents for your corporate gift program,” which gets our product in front of hundreds of corporate execs throughout the country. And usually the talks I’m giving are to associations and industries that can help advance our name.

So I just spoke at a national convenience store conference where they were CEOs of major convenience stores from all over the country. I spoke at the National Confectioners Association twice last year, which was all the players in the sweetened snack industry. I talk to food-shipper organizations, trucking associations, economic development associations. So all of that has been helping to advance the brand, and it gives me something to do until I can really start selling.

Loren Feldman:

Liz, I think I know the answer to this question. But hearing Stephanie talk about her factory setup, does it give you any thoughts about building your own facility to make your own product instead of outsourcing it?

Liz Picarazzi:

No.

Stephanie Stuckey:

It’s hard!

Liz Picarazzi:

No, I mean, honestly, I know this is not politically correct. But I really like my factory.

Loren Feldman:

In China.

Liz Picarazzi:

Yes, we have a great relationship with them. We’ve done some product development. They were really a great partner during the supply chain issues. And as you know, Loren, I spent a good three months a couple of years ago RFPing out our bins to manufacturers in the U.S. I have to emphasize, it was a huge amount of my time. And it came back that, on average, we would have to pay 67 percent more to manufacture here in the U.S. So, no, I don’t have an interest in that.

I would have if you had asked me two years ago, because I really wanted to do that. Like, as an American, I would have loved to have been able to do that. And if it was possible, I definitely would have. But we got that ruled out.

And the other thing is that we’re manufacturers, but yet we’re not. So we’re not like a Paul Downs where we’re fabricating individual custom things with very high-skilled laborers. Ours are modular. They’re ready to install. They’re prefab. So for us to have a very efficient factory that we have a great relationship with is just—I feel really comfortable with that now, having done the research.

Paul Downs:

Yes. If you’re not manufacturing now and you think, “Oh, I’ll just do that,” you’re in for a world of pain. And I think that Stephanie benefited from basically moving into operations that were already up and running. And they needed a ton of work, clearly, but somebody knew how to make the product in the building when you arrived. So trying to go from scratch? Very tough.

Stephanie Stuckey:

I would also add that we have a factory that’s located in the heart of where our main commodity is produced. So it’s a different model. Almost every product we make has pecans in it. And we happen to be in the number one state for production of pecans in the country. So it just made sense for us logistically to have the manufacturing sited right where our main commodity is being produced.

Paul Downs:

It becomes an interesting question: Do you want to locate your business near where the customers are? Or near where the people who know how to do it are? Because there are definitely clusters of skills in various industries in various places. And if you want to locate near the workforce, then the big issue becomes distribution.

And Liz, you’re about to run into this: If you have to ship all over the country, how do you do the installs? So it’s never easy to balance where you make it and where you sell it—and how you get it between the two of them, and what needs to happen when it arrives. And the best thing is to be able to just put something in a box, give it to UPS or the Post Office, and then you’re done.

Liz Picarazzi:

Well, that is what we do.

Paul Downs:

But you have big things. Don’t they need some assembly?

Liz Picarazzi:

They do. But we have assembly videos. We have really good manuals. We’ve actually never had a complaint from anybody in California, or even Hawaii—where we’ve been shipping lately—about the ability to install.

Paul Downs:

That’s great. Good for you.

Loren Feldman:

Stephanie, can you tell us more about those, I think you said, three raises that you gave to the workforce? Was that driven by turnover? Or by inability to hire more people? Or both?

Stephanie Stuckey:

Both—and also just wanting that to be part of our culture, that we treat people with respect. And it was really important to me. When we first purchased the company—I should know the starting wage—it was like $9 an hour. And we have given modest raises across the board. But then what we’ve also [done]—which I think is more important—is we’ve put in a pay scale within a certain period of time, I believe it’s 30 days, they automatically get a bump if they stay with us.

So that was really important as well, was just to keep people, letting them know that there’s a pathway to prosperity, that this is not just working on a conveyor belt or working in the roasting room all day long. You can have a chance to advance. So we’re working with a local technical school to offer skills: everything from food safety certification to forklift training. And so the more you advance in your skills, the more you have an opportunity to be a shift leader, and then you can be a manager. And so far we have been promoting from within for all of these sort of shift leads and management.

We want to delegate more of the duties that the plant manager is doing. And we’re delegating that to folks on his team to give them more responsibility, like procurement of ingredients. So we’re now looking at designating someone in charge of procurement. One person who is just a really stellar employee, we said, “You’re now in charge of food safety. Your job is food safety operations. You’re no longer working on the plant floor.” So really building a team and building a culture where this can be your career. If you come here, we want you to stay.

Loren Feldman:

At one point, you were concerned about an Amazon facility that was scheduled to open. Did that, in fact, open? And has it been an issue?

Read Full Podcast Transcript Here

.png)